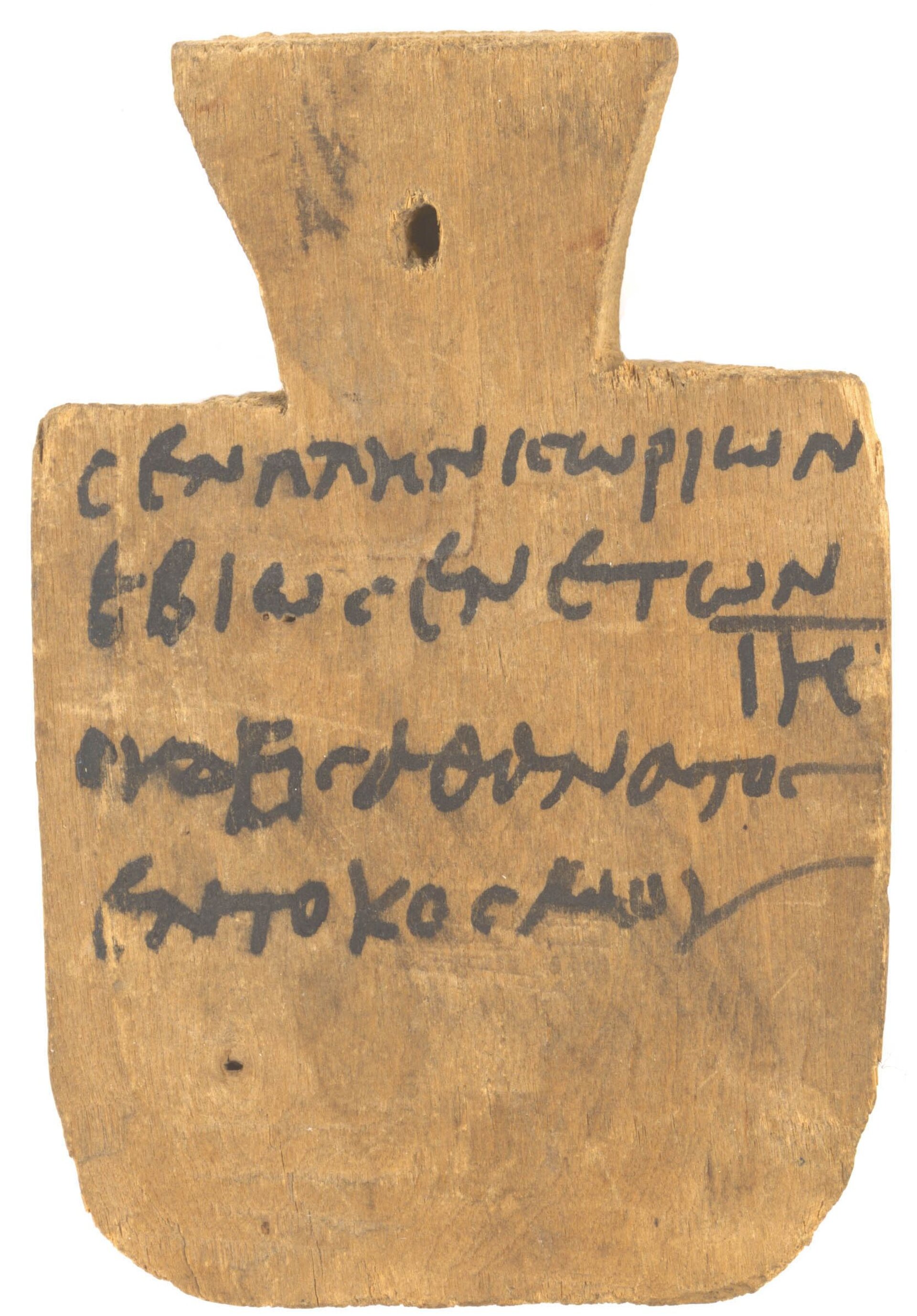

The inscription on this wooden tablet (6,5 × 10 cm) was written in Greek in third century AD Egypt. The official administrative language of Egypt had been Greek since the Macedonian conquest by Alexander the Great (332 BC). When the Roman Empire conquered Egypt (31 BC), the skilled Greek administration was left in place until the Arab conquest (646 AD). It is due to this and the climatic conditions of Egypt that many Greek texts of that time have been preserved in the desert sand.

This tablet, too, had been buried and forgotten, and was eventually rediscovered after about 1600 years. Friedrich Zucker, later professor of Greek and rector of the University of Jena, must have bought it (among several papyri and ostraca, i.e., inscribed potsherds) from the then vivid antiques trade, when the German Archaeological Institute (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, DAI) had entrusted him with digging for papyrus texts in Egypt from 1907 to 1910. He later left those pieces to the Jena papyrus collection.

Among these purchases of Zucker’s, there are three small wooden tablets that are also called mummy labels. They were used for the identification of corpses to be taken to a necropolis or mummification workshop. To avoid confusion, the deceased’s name (“Senplênis”) and his or her father’s name (“Hôriôn’s <daughter>”) would regularly be specified. However, the words of consolation (“No one is immortal in the world”) are unusual, those tablets being attached to the mummy only temporarily, so that the purely functional specification of name and family could have been sufficient. In the mummy labels written in Demotic (a kind of script of the ancient Egyptian language) formulaic sentences are not rare, but they concern the otherworldly journey of the deceased’s soul rather than the grief of the bereaved. At this point, we can only speculate that whoever wrote the text added this sentence out of his personal sympathy or shock at the death of such a young woman.

The words “in the world” are misspelled by the person who wrote the inscription: The article “tôi” should be spelled with Omega (long “ō”) and iota adscriptum, but is actually written with Omikron (short “ŏ”), i.e., “to”, and lacks the iota. It can be assumed that no difference between the two forms was heard in the Greek spoken in Egypt at this time.

Jonathan Trächtler

Bibliography:

Fritz Uebel, Die Jenaer Papyrussammlung, in: Reichtümer und Raritäten. Jenaer Reden und Schriften, Bd. 1, Jena 1974, 150-154. (Beschreibung und Abbildung des Täfelchens)

Herbert Klos, Katalogisierung von Mumientäfelchen, Libri – International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 1.1 (1951), 210-214. (Allgemein zu Mumientäfelchen)